Or, Why New York Marriage Equality Is Meaningless (To Me, Right Now)

Sitting in the New York Senate gallery the evening of June 24th, next to activists I’d been covering for years in their fight for marriage equality, was unquestionably one of the highlights of both my career and my life. As a gay writer who has covered this issue for a long time, and as person whose interracial family of origin began before Loving v. Virginia was law, it was an emotional moment. The tears were flowing freely around me that night, shed alike by the defeated National Organization for Marriage President Brian Brown, and by LGBT New Yorkers who had suddenly received over a thousand legal rights previously denied to them.

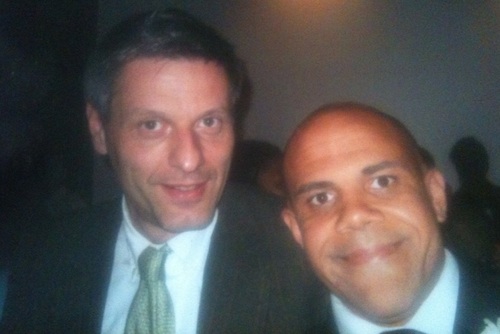

My own tears wouldn’t come for a couple more days, though, when I had to put my boyfriend on a plane that would take him away from me forever. For as wonderful as the passage of the Marriage Equality Act is, it does nothing to save my relationship with the man I’ve grown to love over the past three years.

I’d foolishly made the mistake of falling in love with a man from another country, whose visa will soon run out and whose career can’t move forward in his current state of limbo. If I’d fallen in love with an Andrea instead of Andre and wanted to sponsor her ability to work in America, there would be a clear path on how to move forward and build a life together.

I’d foolishly made the mistake of falling in love with a man from another country, whose visa will soon run out and whose career can’t move forward in his current state of limbo. If I’d fallen in love with an Andrea instead of Andre and wanted to sponsor her ability to work in America, there would be a clear path on how to move forward and build a life together.

Alas, Andre was not a woman the last time I checked, and nothing that has happened here in New York has changed our situation. The Marriage Equality Act is a state law that gives me the guarantee of equal rights under civil law in New York State, were I to marry a hypothetical man I may meet someday in the future. But it does nothing to aid me with any federal civil rights (including immigration sponsorship of a spouse) that could help me with the actual man I already love.

Within hours of returning from Albany, I was helping pack boxes and planning Andre’s pending move back to Switzerland just a few days later. I had long known that by the time anything happens with marriage on the federal level, his visa will be expired and he will be long gone. Real marriage equality was never possibly going to come soon enough to give us a chance.

And yet, it was a stunning punch in the gut to come down from the euphoria of Albany and return to the departure of the man I knew I loved but couldn’t keep in my life.

And yet, it was a stunning punch in the gut to come down from the euphoria of Albany and return to the departure of the man I knew I loved but couldn’t keep in my life.

This is not to say we’d definitely have gotten married, if we’d had the option. I’m a mixed-race African American writer, and he’s a multi-lingual European academic. I’m a Christian and he’s an atheist (though he did take communion the last time I dragged him to church because, he told me, “I’m kind of hungry.”) He teaches architecture history, and I’m far more into my two Franks (Rich and Bruni) than his (Gehry and Lloyd Wright, whom I can barely tell apart.)

Andre’s a tidy Swiss man who inherited his German mother’s impeccable cleanliness, and I am — by stereotypical homosexual housekeeping standards, anyway — a slob. (Ironically, given that he’s from a country known for its watch making and punctual trains, I manage time much better than he manages space.)

And yet, we’ve grown to love each other a great deal. But deprived of any conceivable chance of ever building a permanent life together, we’re leaving each other.

Who knows if we ever would have gotten married anyway? We have wildly different ideas about the institution. I was raised in an American household by parents of different races, whose union was illegal in multiple states when they got hitched. The right to wed the person you love was ingrained in me long before I even knew that I was gay. With both of my parents deceased, I have been quite eager to start my own family.

Who knows if we ever would have gotten married anyway? We have wildly different ideas about the institution. I was raised in an American household by parents of different races, whose union was illegal in multiple states when they got hitched. The right to wed the person you love was ingrained in me long before I even knew that I was gay. With both of my parents deceased, I have been quite eager to start my own family.

My boyfriend, on the other hand, is the only child of two Europeans who’ve been married now for a half-century. Marriage as an institution doesn’t resonate in the same way politically or emotionally with him as it does with me. Adopting children is not allowed for gay couples in his country. Prior to meeting me (while teaching in American universities as he finished writing his doctoral dissertation) gay marriage was not something he’d given much thought to.

But it breaks my heart that we never got the chance to even seriously think about building a life together, because the mere possibility of marriage is simply not a reality at the right time. I’ve shared more with this man than with just about anyone I’ve ever loved. And yet, the chance to grow old and happy (or even old and miserable) together was never really an option.

So we leave each other with broken hearts of what could have been, even though our hearts are still both bursting with gratitude for all we have given each other. I send him back to Europe with my hopes high that he’ll find a job in his field, sadly ashamed I couldn’t sponsor him and give him that opportunity in my country while loving and supporting him in person. I send him off knowing the best way to support his career is to send him away.

And he leaves me so that I can move on with my life, not wanting to stand in my way of wanting to get married and have kids someday. It’s a big sacrifice for us both, but the best chance for us to make each other happy is to leave each other.

And so, all I’m left with is a dim sense of hope. I pray that my heart will survive the departure of this man that I love and that, someday, I’ll be brave enough to love again. I pray even harder that he will find a man in Switzerland who loves him as much I do and who will take care of him in the coming years well as I would have, had I been given the chance. I hope we’re both able to take the love we gave each other, store it in our hearts, and share it with someone else, someday.

Weeks before New York legalized same-sex marriage, I was interviewing an opponent to gay marriage via email. I candidly asked her what advice she had for me, the moron who’d fallen for a foreigner on an expiring visa who’d have to go home: should I try to forget him and love someone else? Attempt not being gay and take a stab at loving a woman instead?

The response I got was, “I do not know your personal situation, but if it involves the potential loss of someone you love very much, I just wanted to say I’m sorry and God bless you both.”

The response I got was, “I do not know your personal situation, but if it involves the potential loss of someone you love very much, I just wanted to say I’m sorry and God bless you both.”

But if she wanted to perform God’s blessings, she’d stop fighting gay marriage, so that the man God put in my path and I might have had the possibility of building a life together, instead of definitely having to part ways.

Albany is a great step for the people of New York. But until Washington takes up marriage equality, it is, practically speaking, meaningless for the pain my heart is feeling right now. It’s also meaningless to the pained heart beating somewhere over the Atlantic, traveling another ten miles away from me every minute.